ECB ENTANGLED WITH BANKS IN POLICY CONUNDRUM

Published by Gbaf News

Posted on August 8, 2014

7 min readLast updated: January 22, 2026

Published by Gbaf News

Posted on August 8, 2014

7 min readLast updated: January 22, 2026

By David Brierley and Saad Sarfraz

Perhaps it’s a sign of the times. The Deutsche Bundesbank is abandoning its profound anti-inflation principles. Head of the Bundesbank Jens Weidmann has suggested that a 3% rise in German employees’ income, which is traditionally linked to productivity and inflation, would be appropriate.

A 3% increase would go well beyond the traditional linkage given the very low levels of inflation in the eurozone. The suggestion has unsurprisingly pleased German unions but distressed German employers.

Peter Praet, executive board member and chief economist at the ECB, has welcomed the suggestion because it might address the competitive challenge faced by economies in the periphery. In those countries, low wages are required to regain competitiveness. Germany famously used monetary union to improve its productivity and competitiveness, thereby strengthening its export performance in the eurozone. Now some of those gains could be given to working Germans instead.

However, the newfound radicalism of the Bundesbank could have other targets.

“I assume the Bundesbank wants to raise wages to avoid deflation in the eurozone, which should also undermine the ECB’s arguments for quantitative easing,” said Hans-Werner Sinn of the Ifo-Institute for Economic Research in Munich, as the Frankfurter Allgemeine reported July 27.

Peripheral dislocation

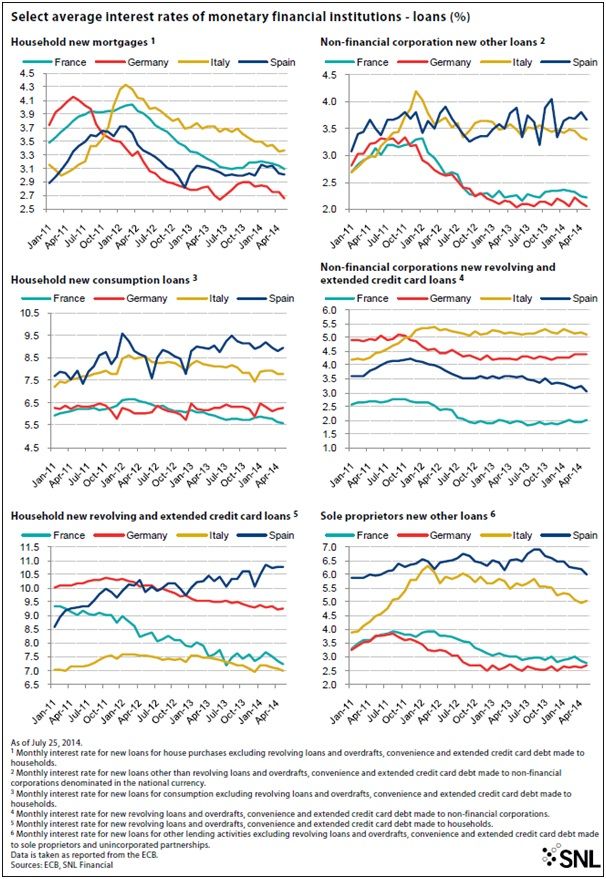

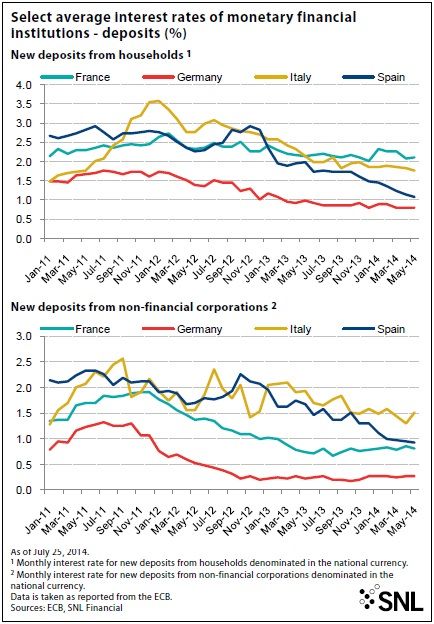

Monetary policy remains deeply troubled in the eurozone, as SNL FINANCIAL charts based on ECB data show.

There is a profound dislocation in the real interest rates available to consumers, businesses, including sole traders, and business credit card users between the two core European nations of France and Germany and the two peripheral nations of Spain and Italy. Identical policy rates are producing very differing results, distorting competition across the euro area.

Only mortgage lending and revolving loans and overdrafts show a less stark differentiation between core and periphery, probably reflecting the different levels of credit risk in the individual MARKETS concerned. Italians, for example, have low levels of personal debt and are frequently property owners, making their credit card usage relatively low risk.

The critical difference for monetary policy is the price paid by businesses to lend and thus INVEST .

Nonfinancial companies in Italy and Spain pay perhaps 1 percentage point to 1.5 percentage points more than their peers in France and Germany for new lending. For sole proprietors, the differential rises to around 2 percentage points to 3 percentage points. Given that this lending is vital for fresh growth and rising employment, this is a serious dislocation of policy. Businesses in the periphery can only struggle to compete with the core and grow.

“Monetary policy is not effective for the whole of the euro area,” Ken Wattret, co-head of European and central eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa MARKET economics for BNP Paribas, told SNL.

“Is the stance for the eurozone as a whole accommodative enough? Although policy rates are pretty much as low as they can go, you still have had an exchange rate appreciation of some magnitude since mid-2012.

“From that perspective, you can argue that rates are not accommodative enough given the persistence of low inflation. Although the policy rate is the same everywhere, the effective cost of borrowing for households and FINANCIAL corporates varies considerably.”

“From that perspective, you can argue that rates are not accommodative enough given the persistence of low inflation. Although the policy rate is the same everywhere, the effective cost of borrowing for households and FINANCIAL corporates varies considerably.”

He added: “The impairment of monetary policy has been slow to be addressed. The main reason for this is risk-aversion in the financial sector.”

Eurozone banks, in other words, are partly to blame for the distorted transmission of monetary policy through the eurozone.

Commerzbank economist Christoph Balz attributes the high interest rates seen in the periphery to high-risk premiums on loans and believes that this is clearly linked to the banks’ asset quality and cost of lending. “The very high percentages of nonperforming loans explain the higher rates in the periphery,” Balz remarked to SNL.

It amounts to a monetary nightmare. The question is what the ECB can do now. This year’s asset quality review and stress test should give banks and MARKETS more confidence about their balance sheets while the ECB has recently announced negative interest rates and the use of targeted longer-term financing operations to help banks lend.

ECB in wait-and-see mode

Both Balz and Wattret think the ECB would now wait to see what effect these measures might bring. Indeed, as Commerzbank observed in an Aug. 1 note, ECB Vice President Vitor Constâncio has said that the central bank “will not undertake any further [measures] until we have checked the effectiveness of these steps.”

While Wattret believes that lending costs might normalize over time in the eurozone, he still thinks extraordinary measures would be required; that is, the significant purchase of assets as an alternative to the traditional conduit of monetary policy through bank lending. Balz foresees a 40% chance of quantitative easing.

The Bundesbank, as noted, has already made its proposal, indicating that it too fears more action will be needed given the very low level of inflation. This reached 0.4% in July in the eurozone, underlining fears of deflation.

Wattret said the ECB had been relatively pusillanimous compared to the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England in terms of extraordinary monetary measures.

Balz added that quantitative easing would only happen once the core interest rate had been cut by a further 0.25 percentage point and if it is clear that demand for TLTROs only amounts to double-digit euro billions. He further pointed out that it was difficult to effect asset price purchasing equitably — for example, buying bonds issued by PSA Peugeot Citroën or Volkswagen AG could disadvantage Opel AG, which is funded by U.S. parent General Motors Corp. Moreover, unlike in the U.S., there is little or no bond issuance in Europe by the small to medium-sized enterprises that are the key to employment growth.

Balz added that quantitative easing would only happen once the core interest rate had been cut by a further 0.25 percentage point and if it is clear that demand for TLTROs only amounts to double-digit euro billions. He further pointed out that it was difficult to effect asset price purchasing equitably — for example, buying bonds issued by PSA Peugeot Citroën or Volkswagen AG could disadvantage Opel AG, which is funded by U.S. parent General Motors Corp. Moreover, unlike in the U.S., there is little or no bond issuance in Europe by the small to medium-sized enterprises that are the key to employment growth.

According to ECB chief Mario Draghi, €1 trillion of TLTRO FUNDING could be made available. This sounds optimistic.

Speaking in late July during their second-quarter results analyst meetings, Spain’sBanco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA and Banco Santander SA, as well as Italy’sIntesa Sanpaolo SpA, appeared especially keen on TLTRO FUNDING .

While neither BBVA nor Santander looked ready to commit to taking the FUNDS , Intesa Sanpaolo said it would do so, splitting the interest rate advantage of the money with its clients. In other words, Italian corporates could benefit from lower interest rates on lending. However, TLTRO funding will not address the cost of risk premium, which peripheral banks are passing on to their customers.

Both BBVA and Intesa Sanpaolo reported figures indicating some interim improvement in their domestic economies year over year but a still tough current environment in 2014 — whereby Spain looks to have undertaken more than Italy to render possible a recovery.

Spanish banks have, as our charts show, managed to reprice much of their deposits to enhance their margins. Italy has further to go and thus a greater opportunity to raise profits while Germany’s banks truly are being squeezed by generally very low corporate lending rates and deposit rates which, Balz said, could hardly go lower.

Although Intesa celebrated the strength of its own first-half 2014 profitability, the outlook for Italy’s banks as a whole remains unimpressive. As Moody’s stated July 15: “Italian banks’ problem loan levels will remain high over the 12- to 18-month outlook period, likely requiring additional provisions, whilst the influx of new problem loans will continue until the economic recovery translates into more tangible improvements in employment, consumer spending and corporate investments.”

There is some sign that the new inflow is improving in Spain. However, given that unemployment is around 25% in the country, similar balance sheet issues will weigh on economic progress and banks’ cost of risk. This effect will continue to feed through to the banks’ lending costs and to the costs of borrowing for businesses in both Italy and Spain. It will also hurt banks’ profitability. The great hope now is that the TLTRO will address these issues.

Explore more articles in the Top Stories category